The Leech Book of Bald

Blackberry.

The oldest known Saxon book addressing plants and herbs is the Leech Book of Bald (c. A.D. 900-950). Although many herbal manuscripts held today are in poor condition from age and wear, the Leech Book of Bald is a "perfect specimen of Saxon work," having strong vellum and in unusually good condition. "This Saxon manuscript...is the only existing leech book written in vernacular" (Rohde, 1974). In old time, "leech" was a word which referred to a medical practitioner, or doctor. The Leech Book "was the first medical treatise written in Western Europe which can be said to belong to modern history" and not classical medicine.

The book was "probably written shortly after [King] Alfred's death, but it is more than probable that it is a copy of a much older manuscript." It consists of 109 leaves and is written in a "large bold hand and one or two of the initial letters are very faintly illuminated". Internally, it contains a collection of "exceptionally fine specimens of Saxon penmanship" (Rohde, 1974). Many pages hold unidentifiable and unknown markings. The books made "reference to remedies of a Scottish origin" and included much folklore (Darwin, 1996).From what can be ascertained, healers at that time likely "relied on the old heathen superstitions, probably from an instinctive feeling...combined with the herb lore which had been handed down through the ages." In the Leech Book, "the virtues ascribed to the different herbs are based in not the personal knowledge of the writer, but on the old herb lore...[it] is the oldest surviving manuscript in which we can learn the herb lore of our ancestors, handed down to them from what dim past ages we can only surmise" (Rohde, 1974).

The Anglo-Saxons of that time had "created a vernacular literature to which the continental nations at that time could show no parallel, and in those days based on a knowledge of herbs (when it was not magic), their position was unique." The wisdom and reverence shown towards the ancient text has persisted up until modern times. In 1903, for instance, in a lecture at the Royal Society of Physicians, much discussion revolved around the book. One doctor lectured specifically on "the remarkable fact that the Anglo-Saxons had a much wider knowledge of herbs than did the [current] doctors of Salerno, the oldest school of medicine and the oldest university in Europe" (Rohde, 1974).

The book was "probably written shortly after [King] Alfred's death, but it is more than probable that it is a copy of a much older manuscript." It consists of 109 leaves and is written in a "large bold hand and one or two of the initial letters are very faintly illuminated". Internally, it contains a collection of "exceptionally fine specimens of Saxon penmanship" (Rohde, 1974). Many pages hold unidentifiable and unknown markings. The books made "reference to remedies of a Scottish origin" and included much folklore (Darwin, 1996).From what can be ascertained, healers at that time likely "relied on the old heathen superstitions, probably from an instinctive feeling...combined with the herb lore which had been handed down through the ages." In the Leech Book, "the virtues ascribed to the different herbs are based in not the personal knowledge of the writer, but on the old herb lore...[it] is the oldest surviving manuscript in which we can learn the herb lore of our ancestors, handed down to them from what dim past ages we can only surmise" (Rohde, 1974).

The Anglo-Saxons of that time had "created a vernacular literature to which the continental nations at that time could show no parallel, and in those days based on a knowledge of herbs (when it was not magic), their position was unique." The wisdom and reverence shown towards the ancient text has persisted up until modern times. In 1903, for instance, in a lecture at the Royal Society of Physicians, much discussion revolved around the book. One doctor lectured specifically on "the remarkable fact that the Anglo-Saxons had a much wider knowledge of herbs than did the [current] doctors of Salerno, the oldest school of medicine and the oldest university in Europe" (Rohde, 1974).

Anglo-Saxon Translation: Herbal of Apuleius

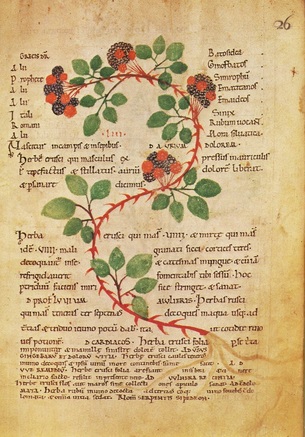

Manuscript page from "Apuleius Platonicus".

Image from Blunt & Raphael, 1980.

The herbal of Apuleius (published originally c. AD 400 in Greece) was "first translated into Anglo-Saxon around the year 1000." In addition, a "finely-illustrated codex, Cotton Vitellius C. III, which combines elements of [earlier, classical Greek herbalists] Dioscorides and Apuleius, can be dated around the middle of the eleventh century" (Blunt & Raphael, 1980). This herbal "was perhaps the first which opened...the herbal medicine of southern Europe" (Arber, 1986).

As in other works of its time, "plants were regarded merely as 'simples'--that is, the simple constituents of compound medicines." Many recounts of the "virtues of the plants are of the nature of spells or charms rather than medical recipes", however (Arber, 1986).

To the left, an illustration taken from a translated manuscript written at the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds (c. 1120) is an unusually naturalistic depiction for its time. It is suggested that there was an otherwise unknown body of naturalistic art or the illustrator was "far in advance" of the time (Blunt & Raphael, 1980).

As in other works of its time, "plants were regarded merely as 'simples'--that is, the simple constituents of compound medicines." Many recounts of the "virtues of the plants are of the nature of spells or charms rather than medical recipes", however (Arber, 1986).

To the left, an illustration taken from a translated manuscript written at the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds (c. 1120) is an unusually naturalistic depiction for its time. It is suggested that there was an otherwise unknown body of naturalistic art or the illustrator was "far in advance" of the time (Blunt & Raphael, 1980).

References

- Arber, A. (1986). Herbals, their origin and evolution: A chapter in the history of botany 1470–1670. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Blunt, W. & Raphael, S. (1980). The illustrated herbal. London: Francis Lincoln.

- Blunt, W. & Raphael, S. (1980). The illustrated herbal. London: Francis Lincoln.

- Darwin, T. (1996). The Scots herbal: The plant lore of Scotland. Edinburgh: Mercat.

- Rohde, E. S. (1974). The old English herbals. London: Minerva Press.